Dust Grows in Time — Tang Yi’s Photography (2011-2023)

2023.07.09 – 2023.08.30

Press Release

Tang Yi: Between the Visible and Invisible

Feng Boyi

After debuting her work in the medium of painting with the 2012 exhibition “A World Lit by Fireflies” at Space Station, Tang Yi turned to photography. According to her, the exhibition marked the beginning and the end of her painting career. In 2011, she began photographing herself after spending considerable time covered in paint. She said, “In photography, I survived.” When an artist completes a creative stage, it may give rise to the idea of starting over. For her, the most crucial aspect of any medium is its ability to effectively convey the intended message, regardless of the medium, whether painting or photography. Perhaps this shift in her artistic journey could be seen as a way of tying up loose ends and moving on from the past and, alternatively, forcing her hand to deal with loss, leading to a necessary step towards closure and reinvention.

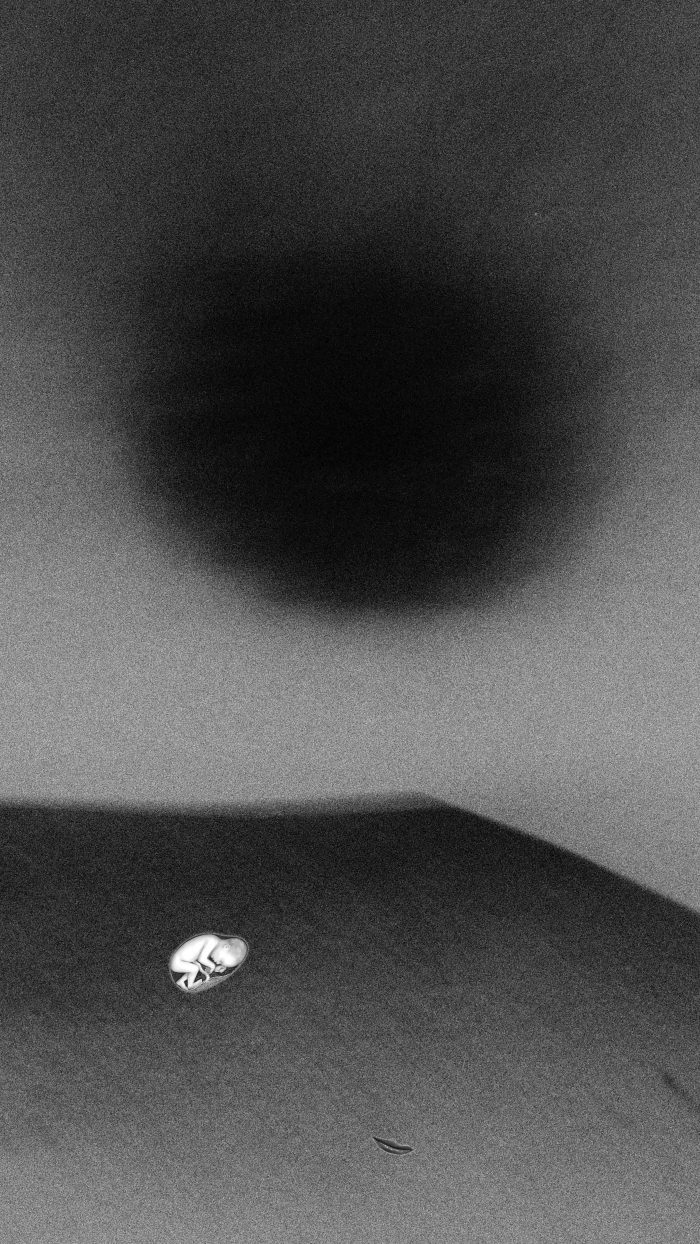

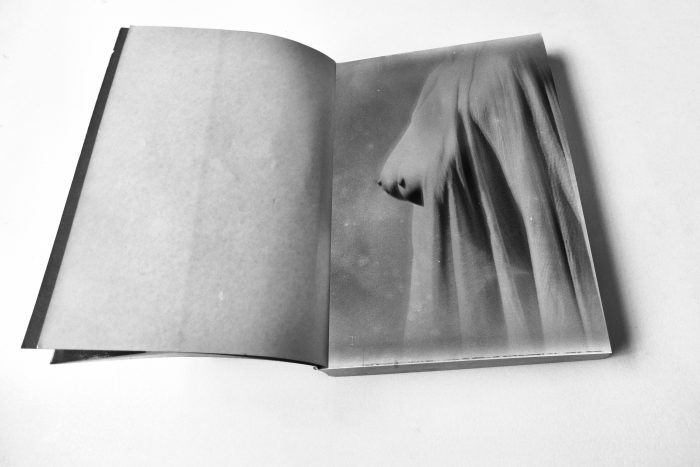

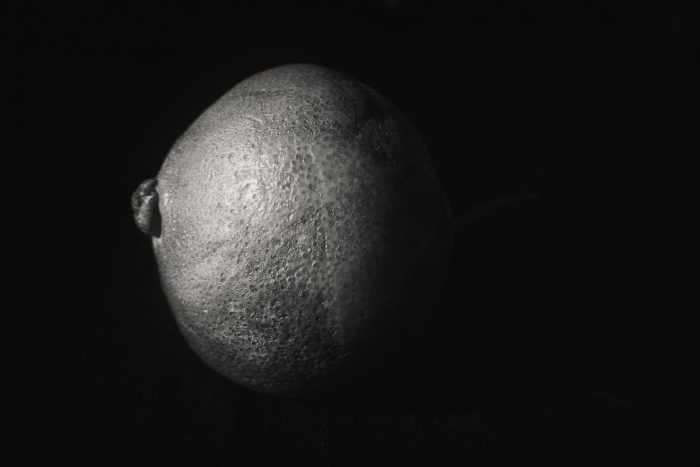

Tang Yi’s photography delves deeper than mere documentation of external moments, as it serves as a tool for her to confront and resolve inner conflicts. Her works frequently explore enigmatic scenes in haunting black and white, focusing on themes of love and relationships. Through her lens, Tang Yi captures the rush of oxytocin that comes with eye contact and the trials and tribulations of love when taken for granted. Each element in her photographs, from the birds to the flowers to the fishes and insects, appears alienated from itself and its surroundings, creating a sense of detachment. Tang Yi’s fictional “I” is more accurate than the real “I”, as she portrays herself as the dust in the shadow of her heart, as seen in her latest work, “Lonely Island“.

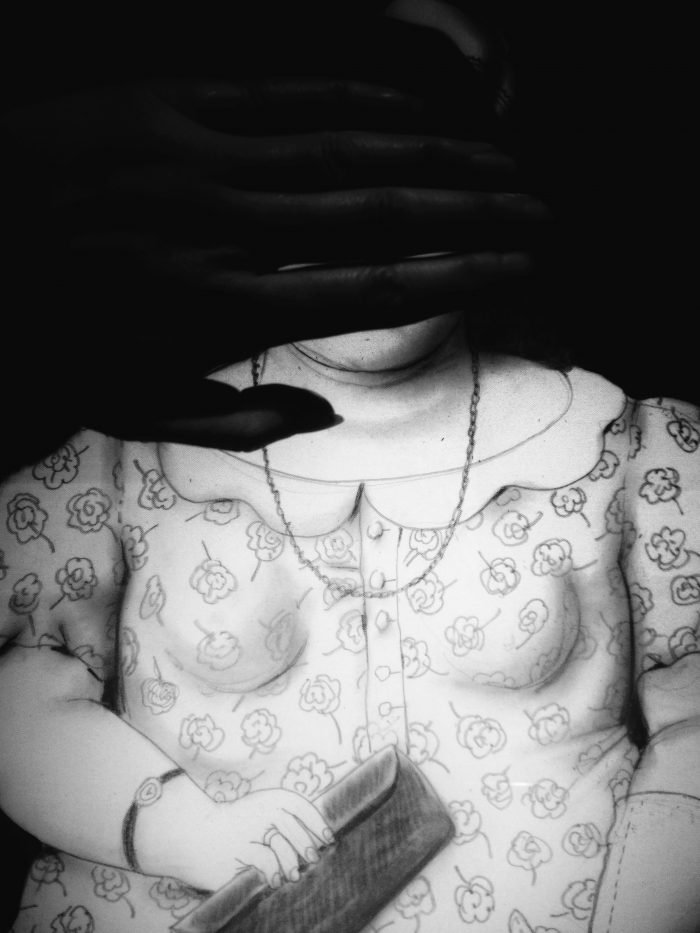

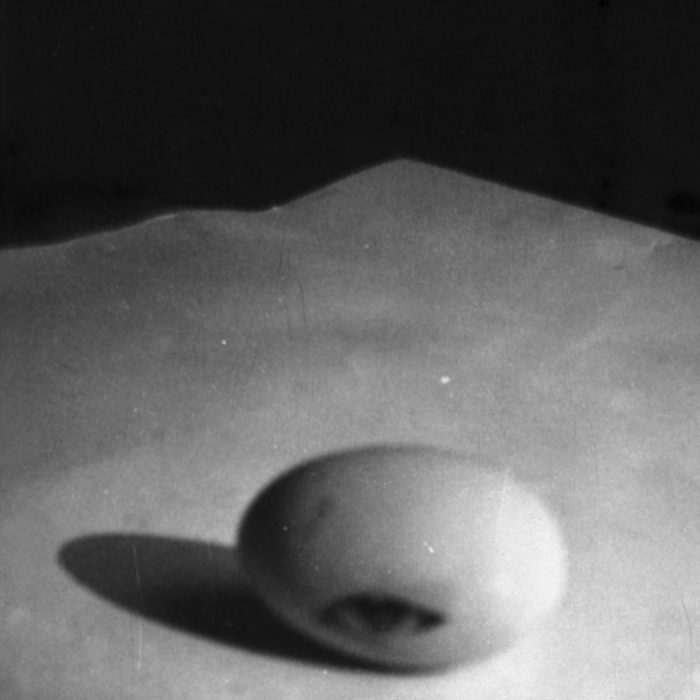

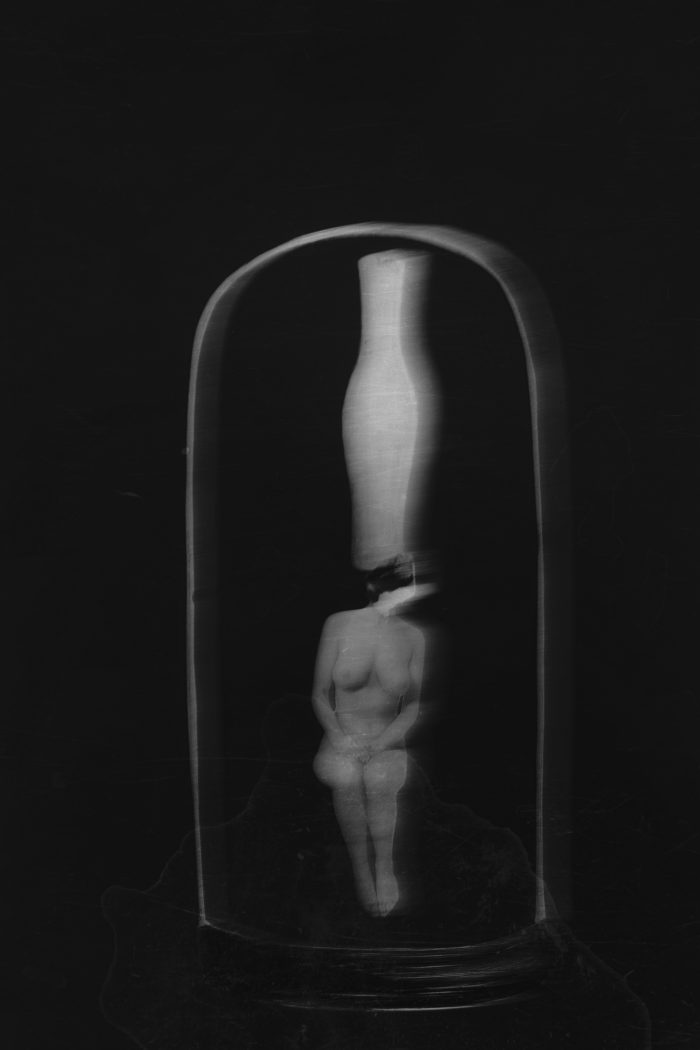

Tang Yi is a cunning genie who challenges how we see the world by creating images that disrupt the order of vision. Her work is a collage of sensual and rational imagery that blends reality and fantasy, using objects like plants, vases, and masks alongside the body, eyes and fetus to create surreal effects. Her imagery brought her most intimate experiences, memories, likes and distastes to light, capturing the complex and often conflicting emotions that come with relationships and portraying them with a compassionate, melancholy, and poignant visual effect. At the same time, her work explores a trembling and treacherous structure endowed between the body, the vessel, and symbols, using the most straightforward photographic techniques to suggest deeper meanings and connections. Tang Yi’s art allows nonexistence to suggest that things once existed. This bridging of the gap created by many jumps creates a smooth logic that encourages us to slow down our thinking and better understand the complex emotions that her imagery evokes.

I believe Tang Yi’s ultimate goal is to discover the presence of “Dust Grows in Time” within each person, tracing the path of their destiny and exploring the delicate intricacies of their emotions, all while nurturing a garden of darkness in the midst of a bustling, secular society.

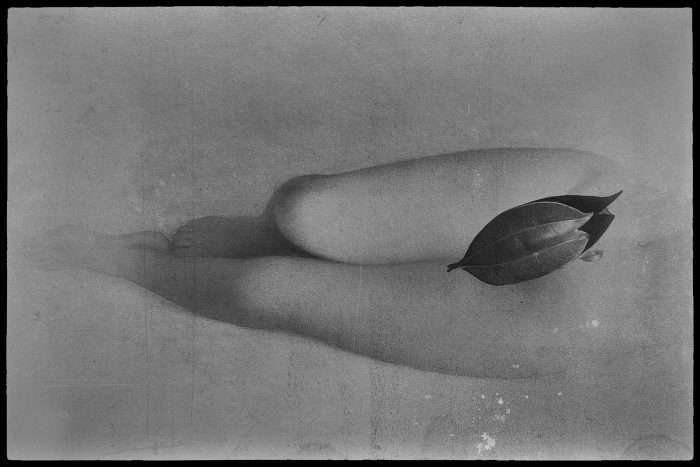

“Body” and “growth” are Tang Yi’s favored themes in photography. However, she is more interested in the process of perceiving rather than just the physical body and growth. This process is a stable, retrospective and reparative growth of orchids that helps heal the missing parts, attain the pursuit of love, and increase self-esteem. In her series of works titled “Love and Art”, she captures the remaining body in a still image, exploring the entanglement of fate and the emotions of joy and sorrow. For Tang Yi, the external manifestation of the body becomes a representation of the self, and the flesh is simply a shell, but the body never forgets. The feelings and shaping of the body also portray the soul in a purer sense. Tang Yi’s “embodiment” shows her capacity to accept her identity and destiny and create a self-contained and ever-expanding inner world, even when virtual reality blurs the line between reality and fantasy through distorted images.

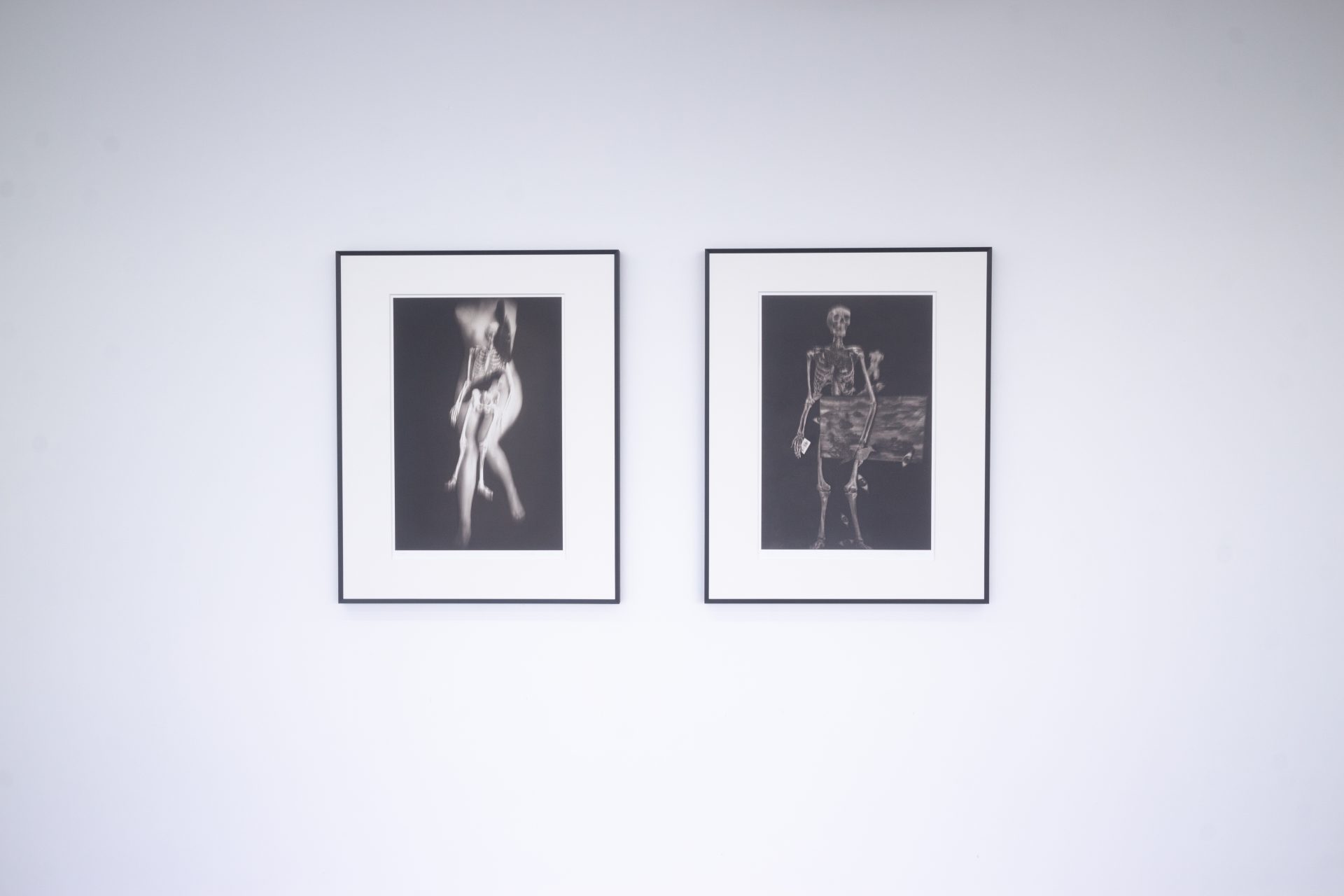

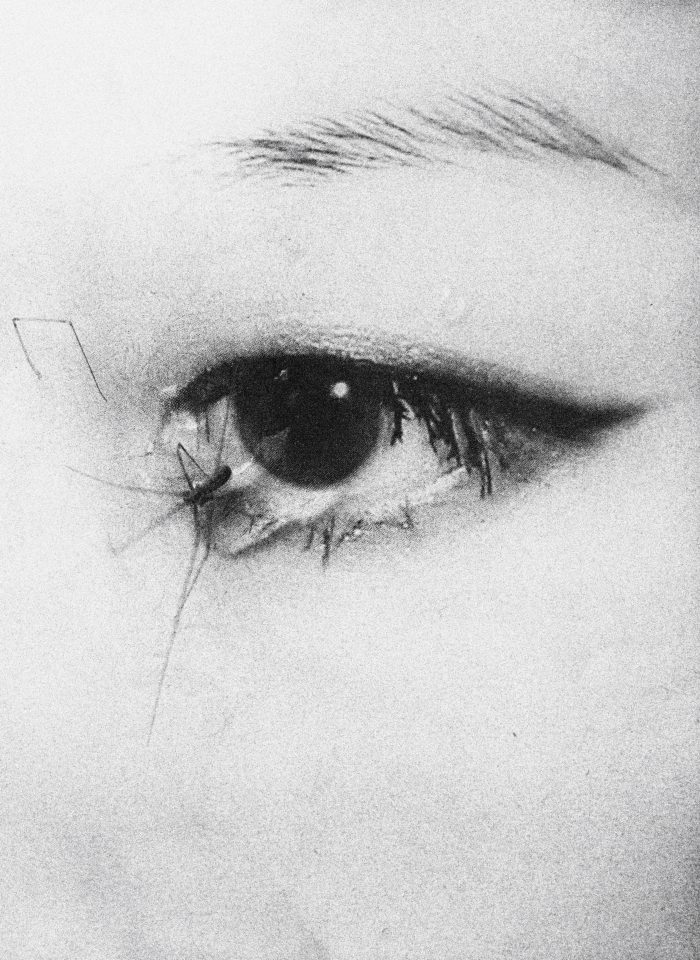

Art can be likened to a dream separated from reality, processing the nature of fiction. To quote Tang Yi, “I don’t capture what I see with my eyes; what can be seen is overshadowed by what cannot be seen”. Both visible and invisible constraints exist within the gray area; external fetters exist outside the body, while internal fetters exist within the heart. Tang Yi’s photography, such as “Listening Eyes“, – placed various forms in different perspectives, including mosquitoes sucking on the corner of the eyes. The eyes are often considered the gateway to one’s inner qualities, but it also reminds me of Gu Cheng’s paradoxical prose: “The dark night gave me black eyes, but I use them to search for light”. Therefore, Tang Yi’s photography resembles “soul-stealing” narrative paintings, where souls are either captured or missing. She often incorporates fragments into the darkness of her images, occasionally revealing haggard visages. She also immerses herself in the trance of The Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara, who has a thousand hands and a thousand eyes, staring at you with a nightmarish gaze. Tang Yi can alleviate the weight of reality through her murmurs and arbitrary expressions without resorting to pseudo-relationships. In her latest work, “When My Soul Meets Yours,” she dissects herself, unfolds the dark interface, and coexists with the devilish skeletons, thus accomplishing the pursuit and manifestation of the supernatural and, ultimately, self-acceptance.

Such a photographic orientation determines the tendency of Tang Yi’s photographs to be a niche private discourse. Nowadays, taking photos and being photographed is a popular activity that allows people to customize their image sources, play different roles, and easily share their moods. This creates a quick and easy way to establish temporary bonds with followers, which can be extended through likes, comments, or retweets. However, Tang Yi’s photography is a clear rejection and resistance to this popular social media trend. She stands firm in her unique artistic vision and is determined to continue creating her own path.

This confrontation between humans and the environment is all caught up in a deep-rooted insecurity, in which the ego is self-destructive, pleasure-seeking, and perplexed with the pursuit of eternity, raising questions like: How should we look at life, death, and love? How should we look at disappearance and reappearance? How should we look at the constant and impermanent aspects of the world? Her “Irma Vep” complex reflects these unanswerable demands of life, which are ultimately shrouded in doubt and uncertainty. Rather than focusing on capturing corresponding relationships, she seeks to create magical images that project reality in a way that challenges the norm and gives voice to self-revelations.