Who cares whose seed it is! It’s my pregnancy.

2008.11.11 – 2009.01.15

Press Release

Acknowledging the obvious: the gestalt of gestation in Xiao Yu’s art

“Who cares whose seed it is! It’s my pregnancy.”

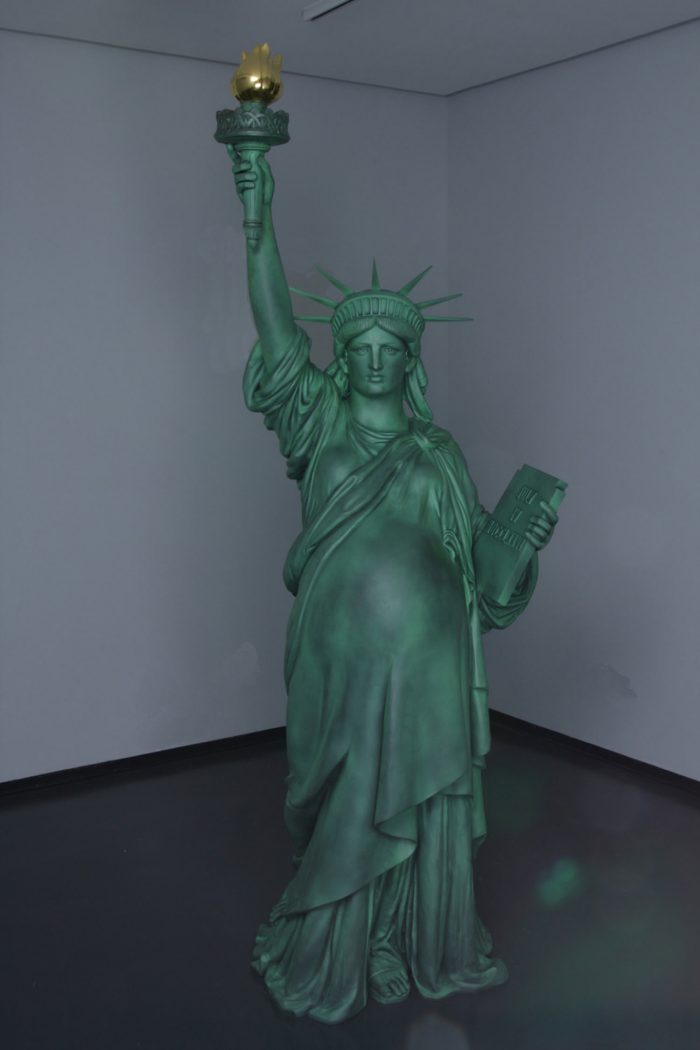

So speaks a dramatic new statue unveiled by Xiao Yu. A human-scale incarnation of the formidable Statue of Liberty, seen up close in an intimate setting, her sight immediately strikes one as both familiar and strange. She is unmistakably pregnant.

This startling discovery presents us with a provocative enigma. As with other memorable artworks in past years, Xiao Yu characteristically orchestrates an instant of shock. The thoughtful viewer must now begin to thread a path through a labyrinth of possible meanings that have been suddenly called into being by what the artwork’s image presumes to propose. Seeking to grasp this figure’s significance, or to rationalize (for instance, in some terms of symbolism) the instinctual impact of its arresting sight, perforce leads one to ponder the state of pregnancy and its range of implications. Other works included in the artist’s solo exhibition likewise play upon the motif of maternity. These variations on a theme amplify our contemplation. The exhibition has cornered us, and won’t let us go. Willy-nilly, we must consider the situation of the pregnant body.

The condition (vividly illustrated by the bold statue’s round, distended belly) promises an impending change in the life of the mother. Questions of fatherhood are rhetorically dispensed with by her cavalier utterance, “Who cares whose seed it is!” The seriously pregnant speaker, instead, draws attention to her own, absolute acceptance of her changed state. Brooking no nonsense, she claims ownership of its reality, acknowledging the obvious when declaring with finality, “It’s my pregnancy.”

The work’s two-sentence title spawns further thoughts. Around the dismissal proposed by its first part, a crowd of objections now convene. The whole structure of civilization, the legacy of human culture reaching back to the stone age, a myriad processes of socialization, family, religion, systems of law, conventions of naming, the efflorescence of cultural life and psychological experience embodied ubiquitously in literature and cinema (for instance) – all of these (and more) arguably run counter to that terse, headstrong dismissal. Who cares? Everybody cares who the father might be. And yet – and yet – must we be quite so literalistic? That a union has resulted in conception, we recognize. Something (to put this in its broadest terms) has happened, bringing about an undeniable result. The title’s second sentence emphasizes an attitude of all-embracing acceptance, regardless of the cause.

Let’s return to the statue (beyond its titular utterance). What is our vicarious experience, when we gaze at it? First, perhaps: an awareness of new challenges. Second: a realization of joy. These two responses (occasioned by the bodily transformation) emerge in thought as dynamically balanced factors. Together, they appear to animate Lady Liberty’s grave stance. Together, they are felt to emanate from her sober visage. In point of fact, these linked qualities – self-awareness and fierce joy – we can likewise discern to invigorate those words ascribed to the pregnant legend. “Who cares whose seed it is! It’s my pregnancy.” Under the guise of flippant brashness, lies joyous awareness.

The pregnant body bears fruit. So does our contemplation. If translated (for instance) into the terms of a changing society, we might read the statue in this wise. Wakeful recognition of society’s radically altered state, joyous acceptance of the imminent new form of life its changed condition promises – these are attitudinal principles encouraged by the work standing before us. They inhere in the figure, as the evident gestalt of her gestation.

If, as a Chinese artist, Xiao Yu might have foremost in mind his homeland’s radically transforming societal milieu, yet for an international audience, the pregnant image is likely to give rise to differing interpretations or responses. Such is art. The artwork communicates its meaning on various levels, partly depending on what the viewer brings to it.

If this solo exhibition’s eponymous statue conveys considerable dramatic tension and comes charged with complex implications, the artist’s sculptural trio of smaller, charmingly stylized, very pregnant female torsos, conveys a perhaps simpler, but no less essential message. These figurines fluently communicate emotional satisfaction. Speaking in the primordially feminine, somatic language of maternity, a celebratory sense of amplitude and gratitude runs through the delectably plump, formal variations with their particular embellishments: one subtly incised with huge butterflies, another sporting a gold-metal bikini, the third, nakedly milk-white (and in fact partly comprised of literal milk powder in the work’s constituent material).

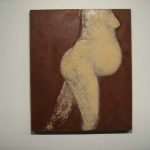

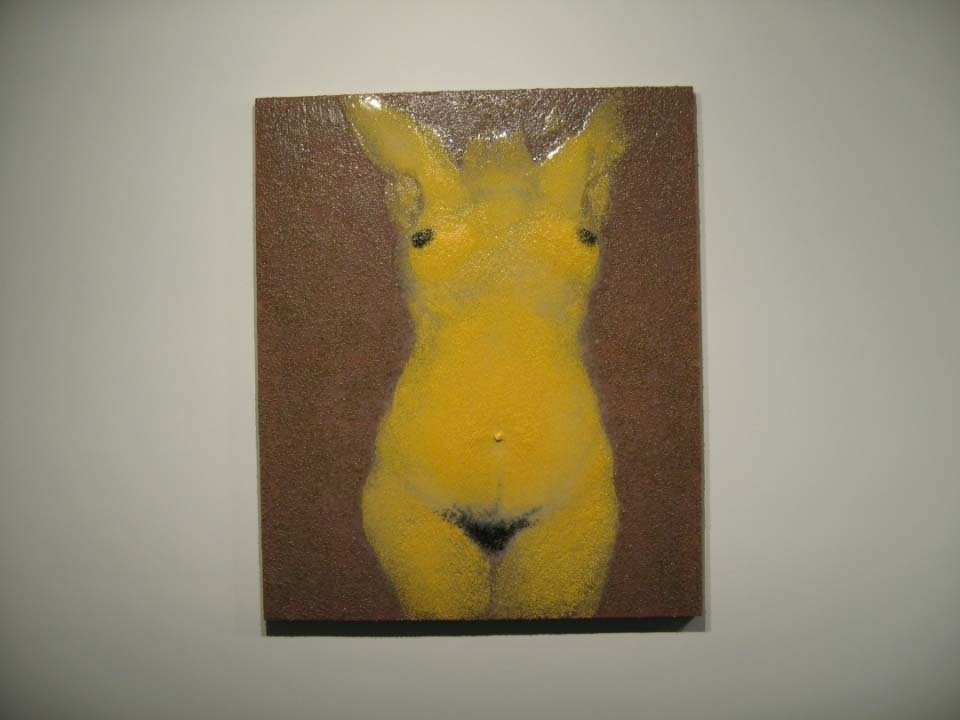

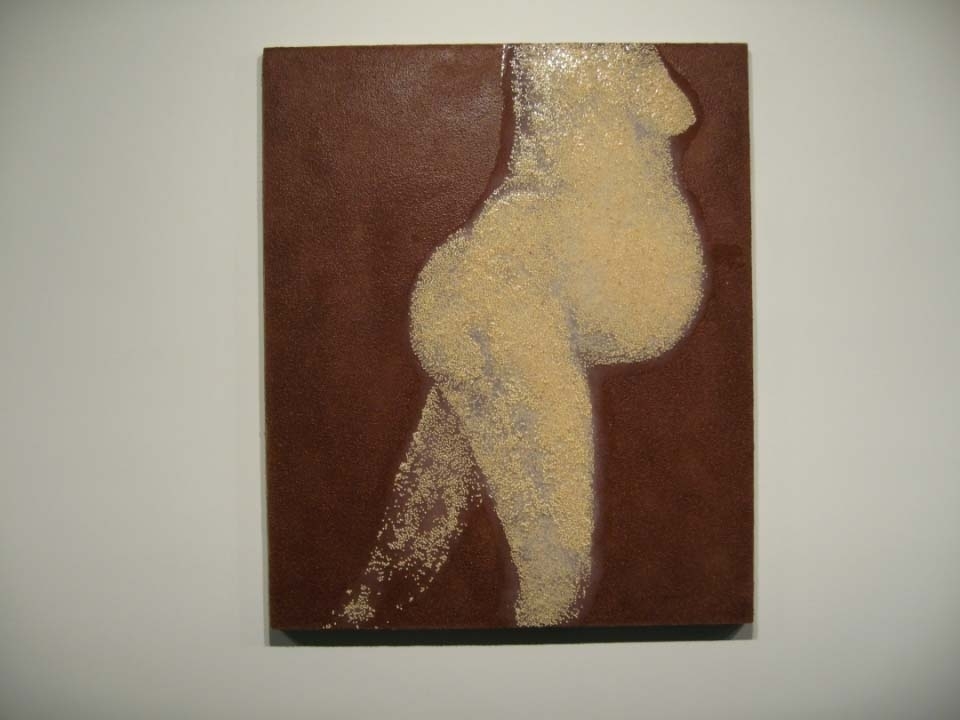

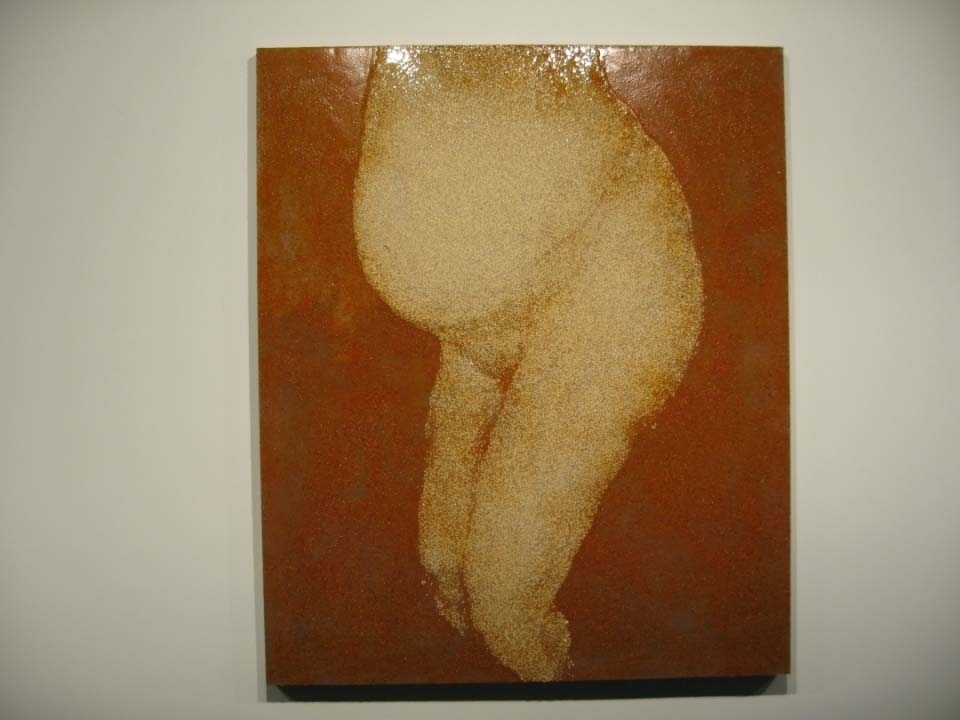

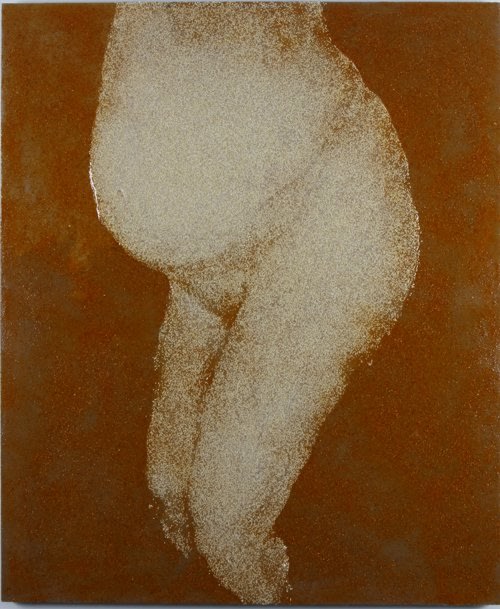

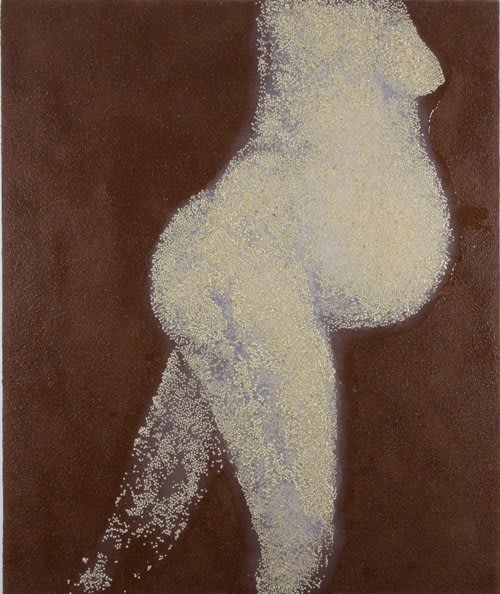

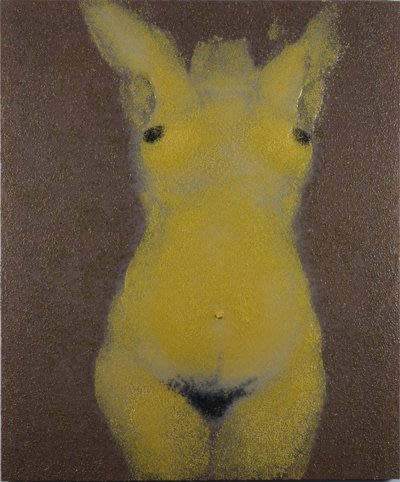

Also on view are a series of unframed, mixed-media pieces, wherein the artist again draws on material foodstuffs (here, comestibles favored by pregnant women) to build up culinary collages. If the Liberty figure suggests pregnancy’s surprise, and if the trio of torsos elicit maternity’s delight, what gist is one to deduce from Xiao Yu’s paintings-consisting-of-munchies? Perhaps they remind how hunger represents life’s original language.

The exhibition is rounded off by an installation in three elements: a possibly incomplete, semi-abstract painting (of shaded ovoid forms); the painter’s habitual stool; and a photograph that captures painter (sitting on stool) amid the act of painting the work on hand. The installation memorializes painting-as-performance. Ongoing process – more than finalized result – is a key idea this dreamy installation brings to light.

In overall effect, the artist’s solo exhibition directs thoughtful attention toward a society (if not indeed a global humanity) poised on the verge of fundamental change. Xiao Yu shows himself to be an artist urgently endeavoring to shake us awake. Nutrition, joy, and society’s self-awareness in its changeful state, are among this timely exhibition’s bywords.

Hu Kaier

October 2008

ARTWORKS

2008

Photograph, painting, artist’s stool

照片,油画,木板凳

250 x 240 x 270 cm(空间大小)

2008

Lamp ,transparent resin ,light-emitting diode

灯,透明树脂,LED

92 x 62 x 62 cm

2008

Sculpture(silica gel,powdered milk), rice, bar table

硅胶、奶粉、大米、bar桌

120 x 60 x 60 cm

2008

Fiberglass-reinforced plastic, picture frame

玻璃钢,镜框

68 x 68 x 10 cm

2008

Sculpture(transparent resin), baby’s chair, silver leaf

透明树脂,婴儿座椅,银箔

90 x 55 x 52 cm

2008

Sculpture(transparent resin, pure gold), Ming furniture, gold foil

透明树脂,纯金,金箔,明式家具

100 x 31 x 45 cm

2008

Sesame seed, chili powder, silica gel

芝麻、胡椒粉、硅胶

120 x 100 cm

2008

Husked kaoliang(sorghum), aniseed powder, silica gel

高粱米、大料粉、硅胶

120 x 100 cm

2008

Mille, black-sesame, anise, silica gel

小米、黑芝麻、茴香、硅胶

120 x 100 cm

2008

Acrylic, duck feathers , lace, “I Love You” streamer ,silica gel

丙烯、羽毛、蕾丝、“i love you”装饰带、硅胶

160 x 120 cm