Burning the Wood: Collection of Du Yuesheng

2011.04.10 – 2011.06.10

Press Release

Victim of Our Times

There are quite a few people who will be very upset to learn that I have written an essay for a catalogue of a show by Zhao Gang. Some of the offended will be close friends; others will be professional acquaintances. “Gangsta Zhao”, as one of the probably upset calls him, is not a universally loved man. And in a situation like the one in Beijing now, where to write is to praise and in which one’s social network is constantly surveiled and gauged, going on record with some thoughts about these paintings could be taken as crime of the highest order.

The first time I actually talked to Zhao Gang was in the At Cafe of Factory 798, sometime in early August 2004. I was interviewing Hung Huang for a story I was writing for the Wall Street Journal. Gang was doing, well whatever it is exactly that he does all day, in this case coming over to interrupt the interview and trade a few jibes with Huang, his old Vassar classmate from the 1980s. We sat for half an hour as he went on about his distaste for New York, the residency space he was building for Jack Tilton out in the eastern suburb of Tongxian, and indeed the good old days when he and Huang were students in the U.S., cut off from a China of which they wanted no part at the time. They had a dynamic quite unlike any other I had observed among Chinese of their generation – and quite similar to that of two middle-aged American college classmates who had known each other well once and then run into each other at alumni events over the years.

I suppose this is the part where I should insert the obligatory paragraph about Zhao Gang’s young, eager role in the Stars Group of the late 1970s, saying how he hung the works on the fence outside the National Gallery at the tender age of sixteen, or how he painted part of the airport mural of topless Dai girls in a purification ritual that proved too racy for the state. I could try to make the case that he was rebel and a hero ever since he was caught in that famous photo dancing with a French girl in sunglasses at a party jointly organized by the Stars and Today poetry magazine (which were really one in the same anyway) on the grounds of the Old Summer Palace in 1981. I could argue that his sense of individualism and myth-making were heightened during his long sojourn in the U.S., and that he is among the only members of his generation who truly understands both East and West, or more humbly, who really speaks native Chinese and native English. But this sort of mythmaking is exactly what Zhao Gang seems to work against in his every canvas.

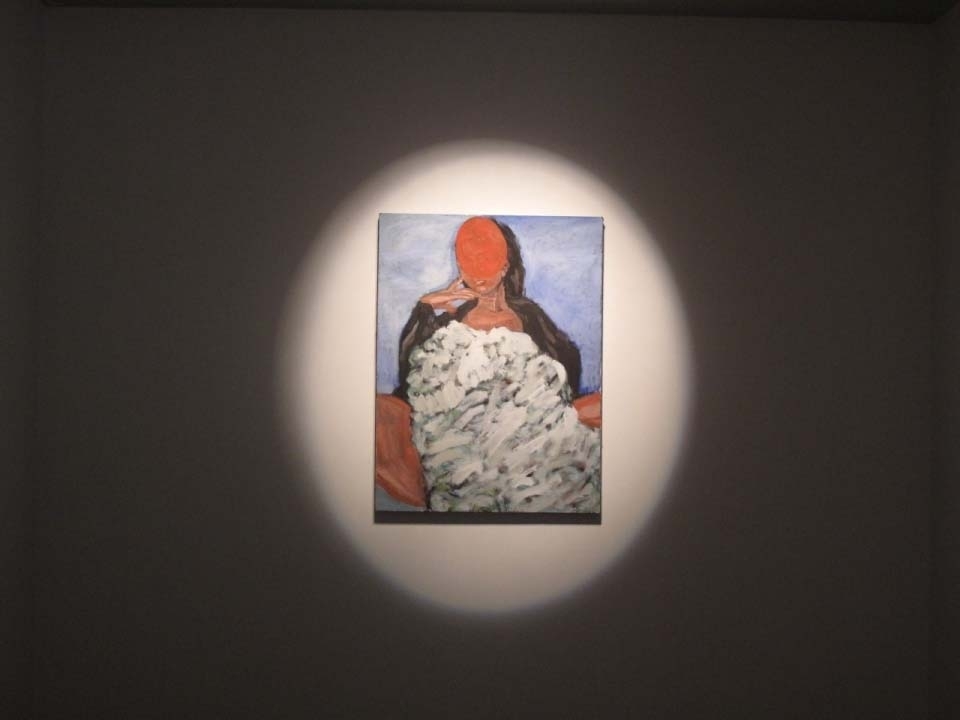

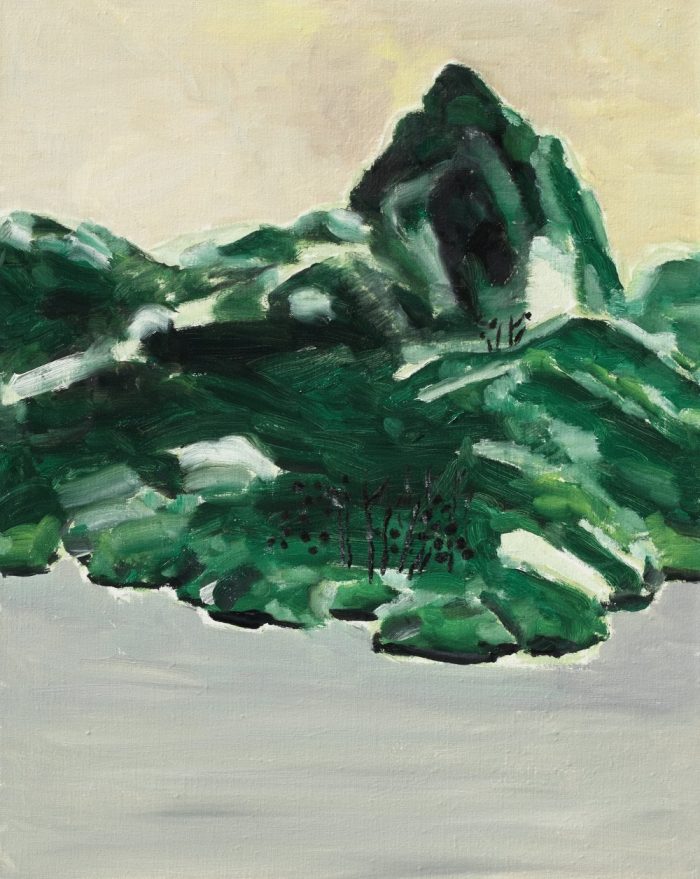

There is nothing complex or conceptual about Zhao Gang’s pictorial planes, and this is their strength. His figurative strategies were thought out well in advance by some combination of Soviet socialist realist pioneers, photographically provoked conceptualists (the Richter-Tuymans trajectory), and German expressionists like Kippenberger whom he learned about only after he started painting like he did. He paints well; no one really denies this. They are not paintings that transform their viewers, although they do delight. Does this imply the “Triumph of painting”, the “return to form” or any similar theoretical whimper recently cooked up to explain just what is the point of making images out of pigment and cloth at a moment when every cell phone has a camera on it? For Zhao Gang’s sake, let’s hope not.

What are these images about anyway? One place to start is the paintings from his Stars period. I saw two of these a few weeks ago at a hasty ten-day exhibition in a private museum in Beijing. They were not even hung together, the lighting was terrible, and they have lost significant amounts of pigment. And yet these two canvases somehow stood out among the entire mass of immediate post-Mao, pre-Deng art as the rare thing with a pictorial vision all their own. One depicted a pedestrian overpass against a background of burnt orange; the other was a geometric interior, a blue sky through a white grid window. Coming from a time when many artists sought inspiration from the fauvists or cubists they were reading about in poor translation and looking at in bad reproduction, these works, with their simple connection to the material realities of their moment, are able to get beyond all the big-picture dreaming of that moment and respond poignantly to the actual situation on the ground. There is a pleasure in them almost as much archival as it is aesthetic – this, we can imagine, is what it was like to look out a window, or cross a busy street, in the Beijing of the early 1980s.

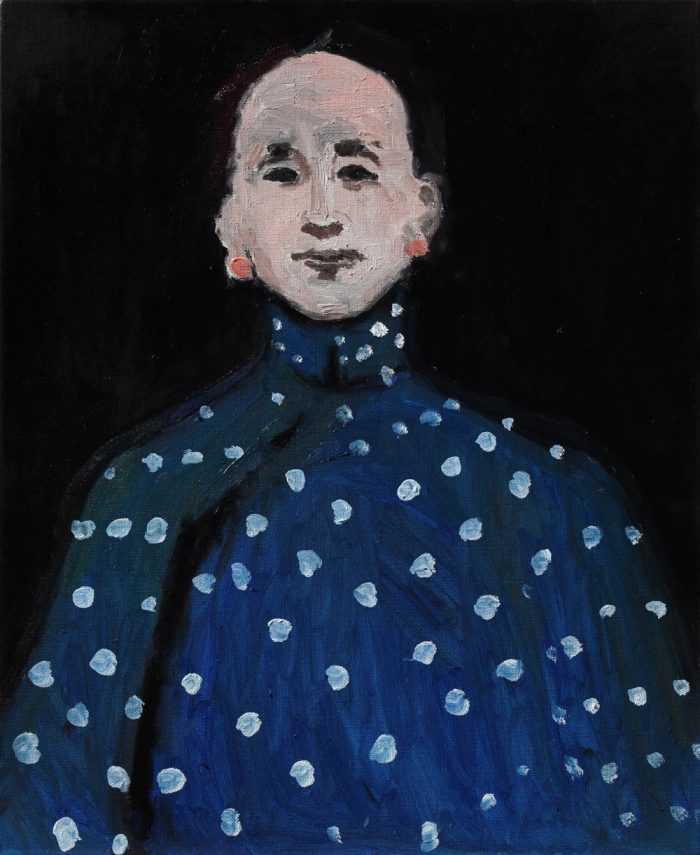

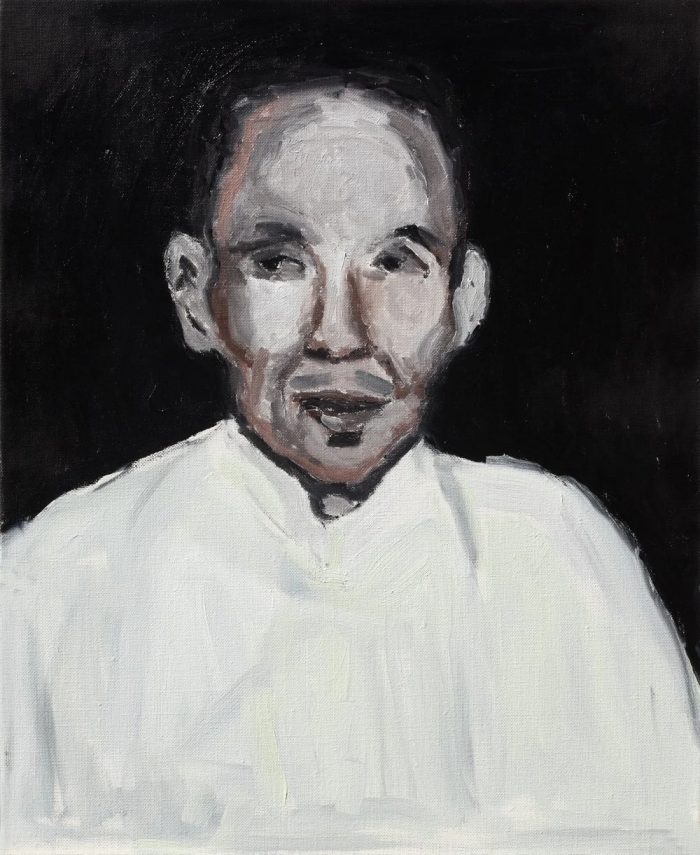

Looking at the works Zhao Gang has painted for this exhibition nearly three decades later, the pleasure remains strangely similar. This group of works returns to themes Zhao Gang has treated throughout his career; put simply, the intersections of politics and history and of love and sex. It is often difficult for members of my generation to be moved by paintings that draw on the visual vocabularies of socialism – we never saw the original thing in play, and our whole introduction to contemporary art in China came via the few 1990s painters who marshaled their ironic appropriation of them into Western approbation. And yet the work accomplished by the diptych in the center of this exhibition is quite unlike anything achieved by the movement dubbed “Political Pop”. In this composition, a band of thirty – some Red Army soldiers stare at the viewer from their monochromatic world, in which the only splash of color is provided by a communist war flag. They are taken from the pages of a mass – market Long March history, its cramped, late 1990s graphic design bespeaking the Party’s still unsophisticated drive to turn doctrine into bestseller. (History books like this, published by mass-market housed that are not quite popular, litter Zhao Gang’s studio.) The artist has been fair to his photograph – the figures are rendered erect, with appropriate solemnity – but he has inserted one damning line of text on the white field of the flag, where normally the name of the detachment would be proudly printed. “Women dou shi nongmin”, reads the inscription in Zhao Gang’s painting: “We are all peasants.”

These six scrawled characters, jumbled together at the far left of the diptych’s left panel, are as important as the entire composition. They seem to be spoken, oath-like, simultaneously, by the entire group depicted. They put the three panels into relief, their linguistic ambiguity forcing the viewer to reconsider the painterly stance that underlies the entire work. The Party would of course not deny that it is a peasant organization, and so the statement retains an aura of political correctness. And yet there is something subversive about a painting in which one line of inelegant text has the power to offset an entire enterprise. A similar effect is achieved in other compositions where the dancers from the model opera “Red Detachment of Women” or heroic workers as depicted in high-Communist sculpture, are rendered with their eyes blacked out by strips like those used to obscure criminal faces in newspapers. Another portrait, based on a photograph from a pulp Mao biography, shows the Chairman standing next to none other than the father of Hung Huang, the aforementioned Vassar classmate who now runs a sprawling fashion media empire. The satirical urge underlying that painting finds expression elsewhere in this group of works, particularly a series based on the real-life heroine of Ang Lee’s recent film Lust, Caution. In these works, as in another group coming from photos of upper-class Chinese wedding in New York during the first half of the twentieth century, Zhao Gang views the fantasy – inducing dynamics of the Republican period through the lens of a contemporary PRC sensibility. Heightening this contrast is the fact that these older wedding photos are paired with inevitably saccharine contemporary peers. Zhao Gang’s recreations of these latter photos, taken from the kitschy magazines that keep the post-Socialist populace entertained, share something with certain paintings of Wang Xingwei, in which mimicry of a blatantly banal set of affects is the best way to talk about themes much larger than the trite love of an ordinary couple.

And this is where Zhao Gang’s paintings leave us: feeling for his subjects as they look for, but fail to find, a way out of the situations into which he scripts them. Perhaps this derives from the artist’s cruelty, or perhaps he knows that we are all – like the Red Army soldiers, like the happy couples, like the great men of history – just victims of our times.

Philip Tinari

Perugia, December 14 2007