JI DACHUN – Gray Moment

2012.10.28 – 2012.12.20

Press Release

Ji Dachun: Searching for an independent point of view

By: Jonathan Goodman

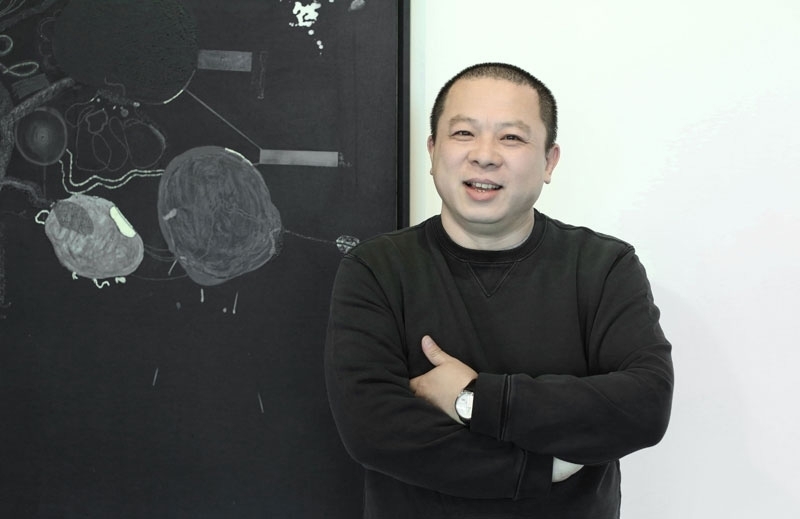

So much has happened to Chinese art in the last five years, it proves hard to generalize. Yet it is fair to say that there has been a general return of artists to China from New York, where they enjoyed considerable support and fame for roughly two decades. These artists were thoroughly public in much of their work, and many remain influenced by Western postmodern practice, although the recent increased interest of many young artists in traditional ink painting shows a decision to return to traditional Chinese art practice and, to an extent, a turning away from western postmodernism. Yet, in Chinese art, the rule is often clarified by the exception. Ji Dachun does not fit this description, neither in his work nor in his life. Born in Nantong in 1968 and educated at the CAFA in Beijing, he now lives and works there. He has never visited the US, and his drawing and paintings prove unusual to the point of eccentricity. Earlier works consist of fey, idiosyncratic objects and creatures that play off a troubled appreciation of nature; birds are plentiful but strange, and flower gardens are drawn extended from a single branch of a tree. But there is also much rawer material to be found in Ji Dachun’s art; teddy bears engage in masturbatory activities, a middle-aged woman carries a basket of skulls, a lamb hold in its mouth a severed, bloody hand.

These images refuses to lie down and play dead-indeed, they are very much alive in the sense that their surrealist power to undermine our expectations (western and Asian both) amounts to a refusal to be openly influenced one way or another. The imagery presented is a hard lesson in imagistic independence; in a deep sense, they are postmodern because they evade the call of either Ji Dchun’s own culture or the western preference for conceptually developed pictures. Instead, the isolated images fit into a larger scheme; they are self-sufficient statements whose irregularities undermine the audience’s preference for easily understandable, immediately beautiful paintings. It would be much easier for Ji Dachun to make work that plays well with our expectations; however, he subverts the genre, creating art whose physical beauty touches upon decay and flat affect. In a time when it has become cliché to speak of dual adherence to traditions from different cultures, Ji Dachun address the sheer awkwardness of the meaning, no matter what legacy he choose to apply. There is no quotation of great art in his work, nor is there any significant bias toward a particular culture. Flowering blossoms are rendered absurd by the presence of a small house with a smoking chimney on a branch. More provocatively, a reddish-pink erect penis, complete with gonads, sports a tiny crown on its head. As viewers can see, the possibilities are endless because Ji Dachun refuses to have a conversation with any particular kind of reality. Instead, he calls upon the sheer randomness of nature and culture.

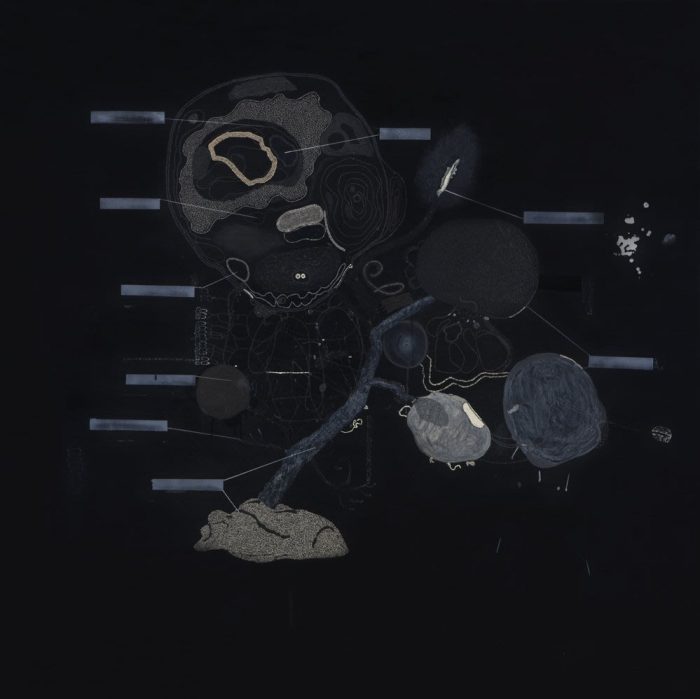

As a result, the absurd may be a particular lens through which we can make sense of an essentially unexplainable body of work. For this writer, it is refreshing not to have to trot out the near cliché of dualities and cultural inferences that bias the audience in one direction or the next. Generally speaking, we notice the orientation of imagery toward decay and death; in Rococo (2006), for example, it looks as though boned are connected to each other by organs that function as grisly nodes. A kidney, for example, sprouts from a thin, curved support, while an intestine is seen joining two bony lengths that simply end in space. It is a slightly disturbing picture that makes no immediate visual sense-hence our return to the absurdist features of the painting. No theory of cultural influence can explain away Ji Dachun’s decision to work the way that he does. Instead, we must rely on the motion that every time he makes a work, he paints on a clean slate- no preconceptions muddy the field of his imagination.

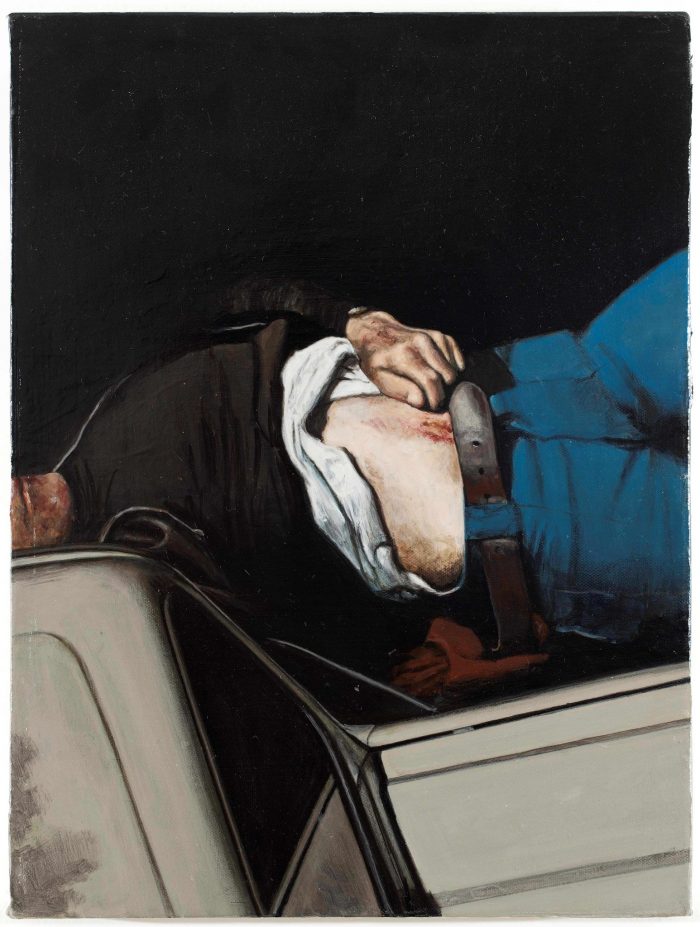

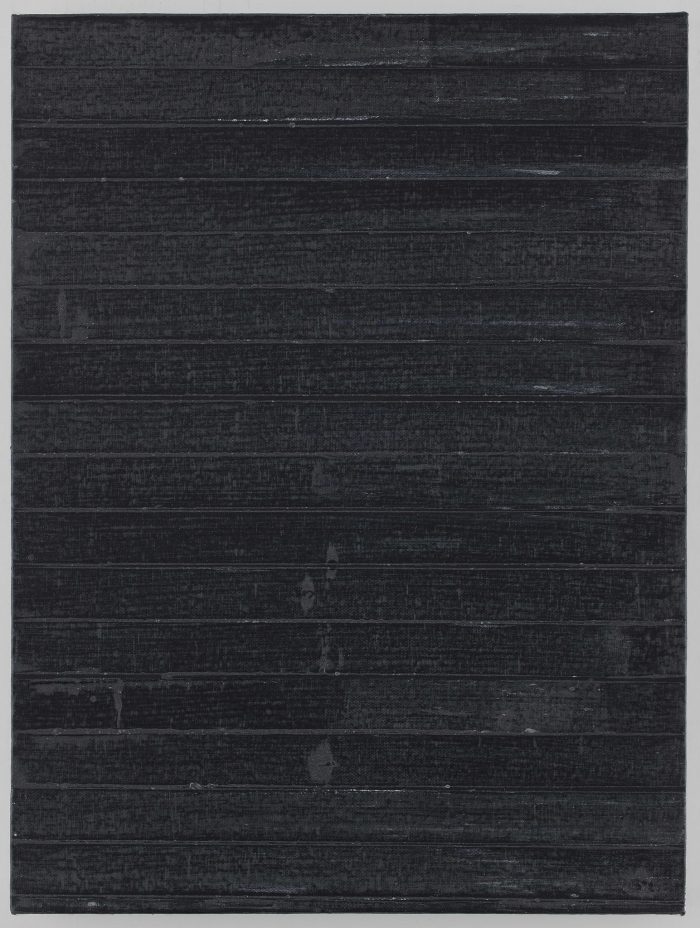

We can remark on the generally ominous quality of much of Ji Dachun’s art, but even that perception simplifies the complexity of what the artist does. In the more recent paintings, he has been working with more involved imagery, sometimes against very dark backgrounds. But the conundrum remains the same; his pictures resist conventional reality rather than aligning themselves with traditional meaning. This may well be the most important path to take in an era of globalism, when it is often hard to say what culture an artist comes from. Ji Dachun may not have consciously chosen his style, but his art represents a principled refusal to take sides. In this way, his alignment is neutral, proving compelling to any individual interested in contemporary art.

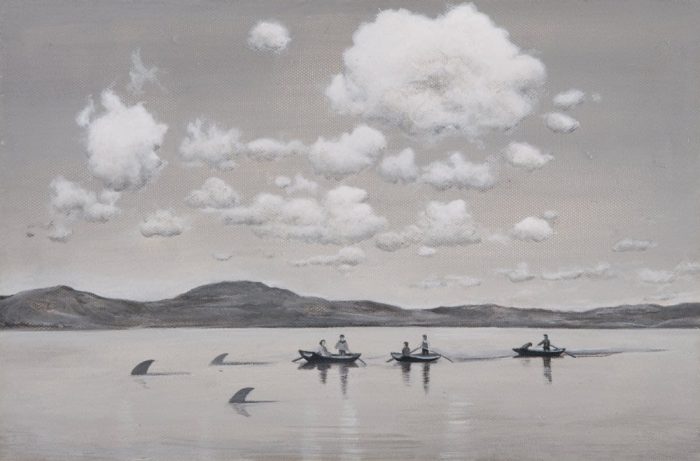

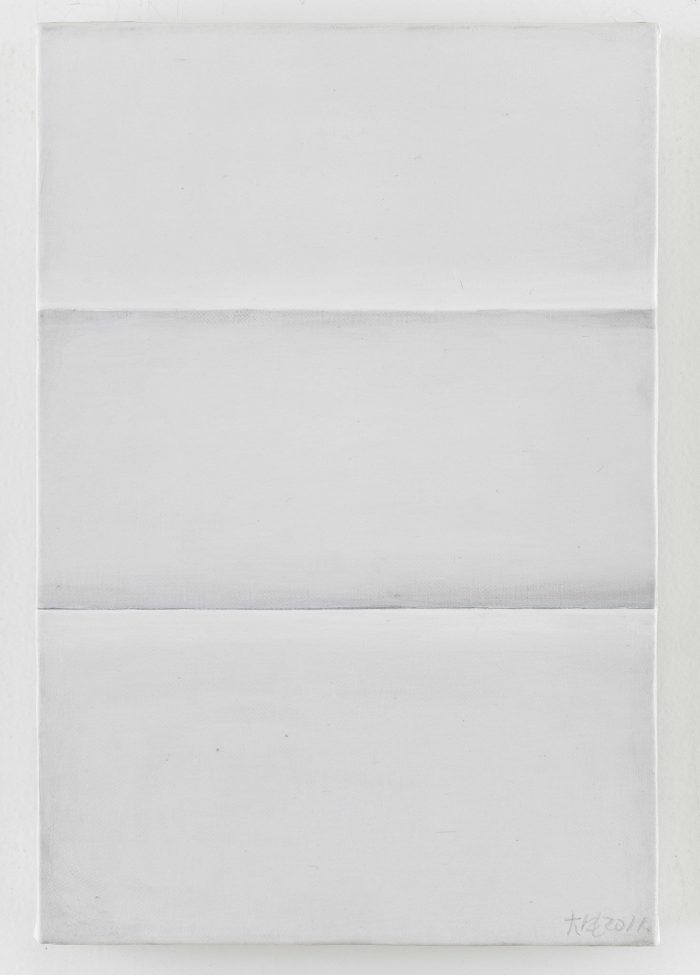

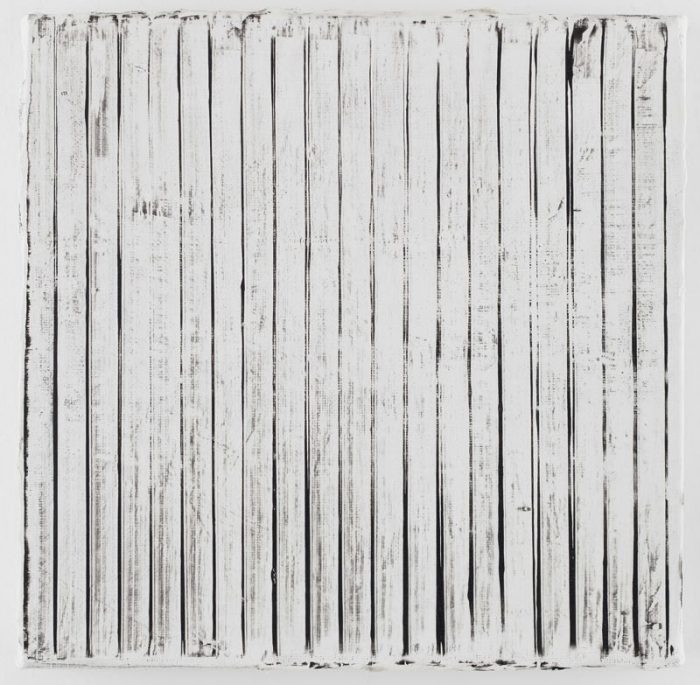

In a couple of landscape drawings and rock studies, Ji Dachun deliberately undermines the landscape of traditional Chinese ink painting. Indeed, in some cases the line is only faintly visible, as if to lighten the conscious burden of historical ink painting. If we can say that the artist consistently undermines the ink genre’s paradigm, it is particularly interesting to see him create a study that demands concentration of a non-cultural sort. Most viewers hold a general sense of Chinese nature painting as inspired and visionary, and Ji Dachun does not disappoint expectations. And it must be said that the drawings do form part of a dialogue with other cultures, just as the early paintings do. The ghostly implications of Ji Dachun’s art reiterate the implicit problems of a historical palimpsest-painters paint versions of earlier painters with conscious awareness. Perhaps, by refusing any easy identification with previous culture, Ji Dachun is emphasizing his own identity in a legacy whose great achievements occurred hundreds of years ago. In As Scenery Disappears, We Disappear (2011), we see an approximation of a landscape, again reduced to what amounts to bare bones: the description of a mass of rock without detail or embellishment. This refusal to seduce the audience amounts to a rebellion toward art in general, for Ji Dachun’s work proposes a kind of no man’s land, where the absurd touches upon the ungainly or even the inappropriate. It is his refusal to commit himself-to culture, to beauty-that makes Ji Dachun such a contemporary artist.

This refusal is based on the far-sighted principle that we cannot go back but must move forward, toward a language that will reflect the critical aspects of our time. As a writer I am concerned to find meaning and symbols in the works that I see, but Ji Dachun’s art resists contextualization. This refusal is part of his aesthetic. It is a highly interesting stance because much art is based on an agreed-upon acceptance of content, yet the artist refuses to present an image that is easily shared. Only the title-As Scenery Disappears, We Disappear, gives us the truth of the image, it becomes clear that the work originates in a time when the environment is lost, and all that we possess is the hard, harsh bareness of stone. It seems we are looking at a damaged aspect of nature, which, interestingly, possesses a skeletal beauty linked to the mortality that is part of our awareness. Here, as happens frequently in the work of Ji Dachun, we look beyond the picture itself to establish a point of view that supports the image.

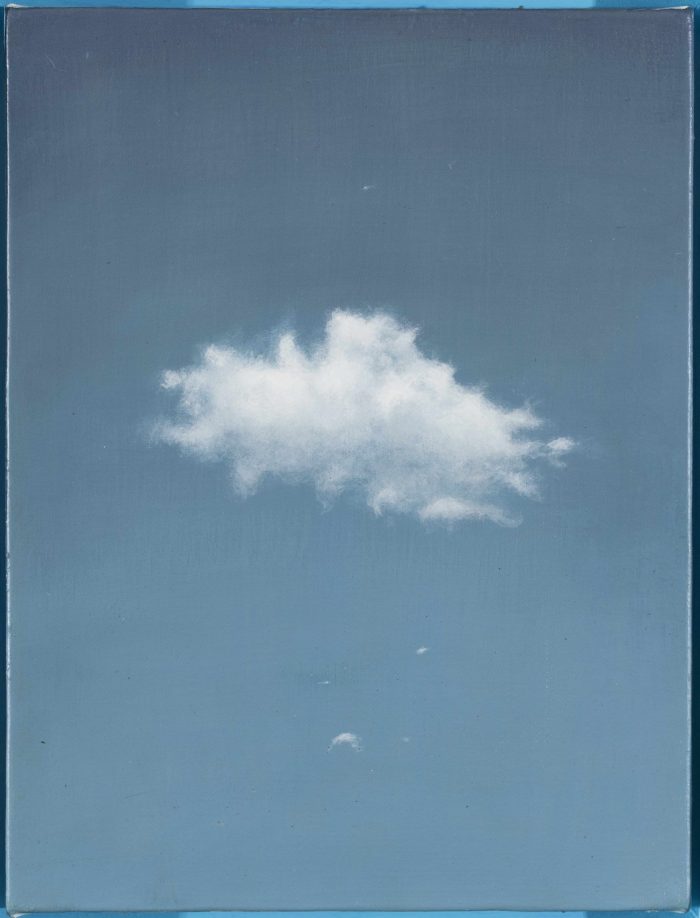

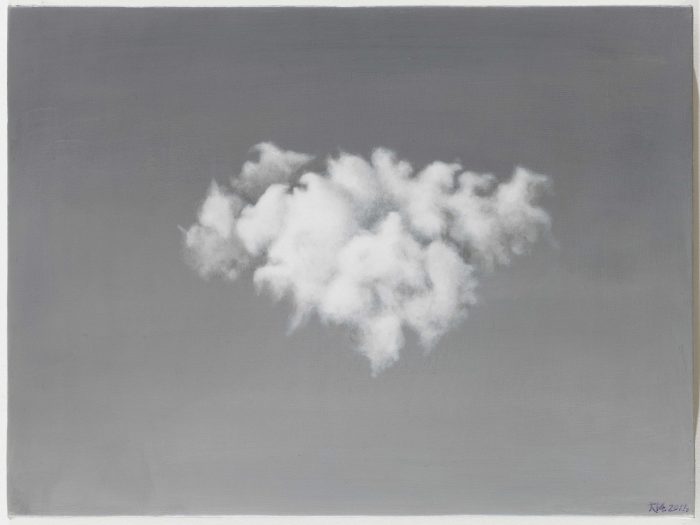

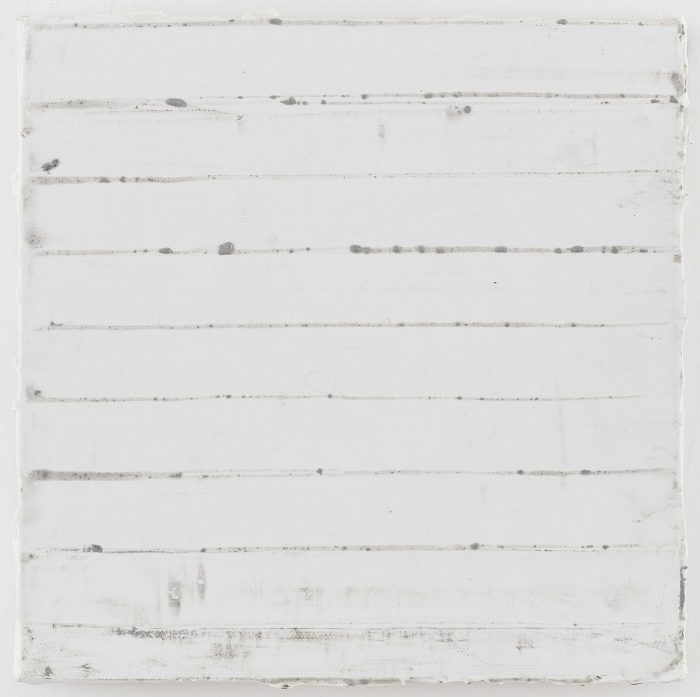

Plastic Brain (2009) looks like a medical image for a surgery textbook – various round circular shapes hang off of a branch of some sort, held against a black background. Little labels with lines pointing to particular parts are empty, as if were up to the viewer to fill in the blanks. The entire work seems incredibly precise, yet we never are given a real clue to what the imagery is about. It may simply be that the image has to do with the limits of knowledge, as if the image could not completely convey the complexity of experience it is supposed to represent. Some of the squiggle and blotches, organic in nature, might remind the American viewer of the work of Terry Winters; Ji Dachun’s art, however, does not easily lend itself to quick comparison or identification with another artist. No Scenery (2012) is exactly that: a series of scribbles and rough netting that puts forth little beyond what can be descriptively recounted. Perhaps Ji Dachun’s determination to strip his pictures of reference is key to understanding his creativity. There is real intelligence in his wish to disassociate from externally imposed meaning, for it is a way of claiming one’s own ground. In a heavily crowded playing field, artists’ attempts to find room to express themselves may require a certain idiosyncrasy. Such an idiosyncrasy concerns Ji Dachun on the highest level.

By concentrating on an emotionally flat affect in his art, Ji Dachun shows us a world that is essentially stripped of its traditional props and supports. The sometimes grim fascination we experience in looking at his work is not so much the consequence of a political stance as it is the expression of an anomie many people might agree with today. With all the artists, gallerists, and writers around, in addition to the many residencies, it might be thought that this is a grand time for art. But intelligent artists like Ji Dachun may know better; they divorce themselves from the crowd in order to make art whose implications are realistic rather than utopian. As a result, we see images that reflect the spirit of the time, which, one acknowledges, is not without its difficulties. Yet it would be a cliché to set Ji Dachcun up as a savior; instead, he is someone different, the proponent of a diffident gesture. Ironically, his art may last longer than that constructed in a rhetoric of large gesture. Certainly, his art is memorable in its austerity. It is an achievement that spells out a lesson of its own for the present. We need to acknowledge the intricacies of cross-cultural influence even as we minimize the impact of one culture on another. This two-pronged approach is not a weakness but a strength – as we see from Ji Dachun’s art.